Processes and Threads - Discourse on Concurrency, Part I

what “concurrency” actually means

The simplest way to distinguish between concurrency and parallelism is that concurrency is about dealing with multiple things at the same time, whereas parallelism is about doing multiple things at the same time. Concurrency relates to structure, whereas parallelism relates to execution.

Rob Pike brings up a great example in his 2012 talk Concurrency is not Parallelism. Suppose you had a gopher whose task is to carry books from a pile and move them to an incinerator. We could add a second gopher to speed things up, and indeed, this would be an example of concurrency, since we’ve restructured the problem. If we think about a gopher bringing books from the pile to the incinerator as a procedure, then we now have two procedures running. In practice, however, these two procedures may not run simultaneously (i.e., in parallel). It’s possible that one procedure could be running while the other is paused, for example. The design of this program is concurrent, but we haven’t said anything about its execution. If there is only one CPU core available, then these two procedures cannot run in parallel, and their execution will have to be interleaved in some way. But if there are multiple cores, we can place each procedure on a separate core and have both procedures running simultaneously to achieve true parallelism.

Sequential (non-concurrent) design

One possible design of a concurrent program that uses multiple gophers

One of the more obvious benefits of concurrency is performance. Tasks can be completed faster by handling multiple things at once rather than doing one task at a time in a linear fashion. One of the less apparent but still important benefits of concurrency is that it makes it simpler to express certain ideas in your program than if you were to design it sequentially. For example, distributed systems are often designed with a “master” node that coordinates multiple “follower” nodes. It’s common for a master node to send health checks to the follower nodes to ensure that they’re still up and working, and waiting for a reply from each of them. The sequential way of implementing this would involve having to regularly stop whatever the program is doing, send the heartbeat, wait for a reply, and then continue. In this case, putting this logic in a separate routine running in the background on the master node simplifies the code and also makes it easier to understand.

threads

The execution of a program is composed of two major components: processes and threads. A process is an instance of a program running on your machine. For example, your web browser is a process. Processes don’t execute as independent units, however. Their execution is composed of one or more threads where the program’s logic runs. By default, each process spawns a thread on which the program runs, known as the main thread. This main thread can then spawn additional threads throughout the program’s duration.

shared resources

Threads running in the same process share everything that the given process owns. This includes, but may not be limited to, memory, file handles, device handles, sockets, etc. One of the most important implications of this, perhaps even the cornerstone behind the concept of multithreading as a whole, is that concurrent threads can and often do interact with the same data. This can lead to a complex class of bugs known as data races, where multiple threads concurrently attempt to modify the same variable or data source, causing that variable or data source to be in an unpredictable state afterward. In fact, in languages like C++, multiple threads modifying the same data is considered undefined behaviour, meaning that in theory, anything could happen. Data races will be explored more in a later section of this Discourse.

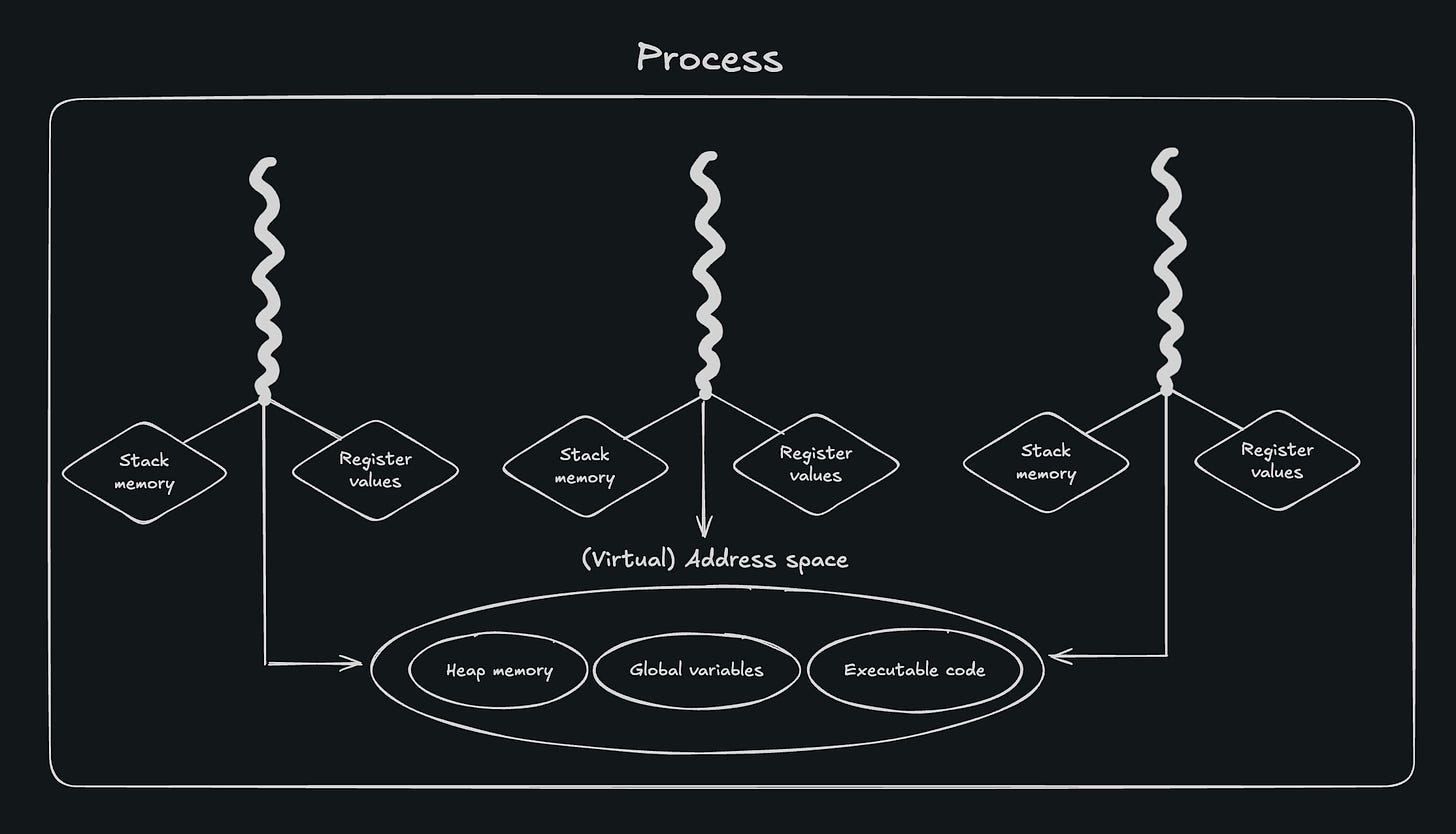

Threads running in the same process share the same address space. Namely, concurrent threads share the same heap memory (dynamically allocated variables), global variables defined in the program, and the program’s executable code itself. Threads do not share the same stack space, and each thread has its own set of register values, such as the program counter (used to identify the next instruction for the CPU to execute). Additionally, threads can utilize a special kind of storage class known as thread-local storage. Variables defined within thread-local storage exist as a unique copy across all concurrent threads. In contrast to automatic (stack-allocated), dynamic (heap-allocated), and static storage, thread-local variables are defined in every thread, with each having its own copy that it can modify freely, independent of other threads. You could think of it as a static or global variable that is local to each thread.

Additionally, each process running on a machine has its own virtual address space and page tables, which are shared among each of its threads. Since virtual memory is scoped at the process level, two processes can refer to the same virtual address but be referring to different physical memory addresses.

scheduling, and how threads achieve concurrency

Notably, even though a process can have multiple threads running within it, only one thread at most is ever running at any given moment for each CPU core on the machine. Similarly, a CPU core can only run at most one process at any given moment. This means that when multiple threads are running concurrently, the operating system must have the active threads take turns executing to allocate the necessary resources (such as CPU cycles, memory, or I/O devices like network links) among them. Likewise, processes must also take turns running on the various cores present on the CPU. These are both managed similarly by an OS module known as the scheduler.

The scheduler can take one of multiple approaches for resource allocation among threads. FCFS (first-come-first-served) is relatively simple; it allows each thread to run to its task’s completion, one by one. The problem with this approach is that it compromises substantially on fairness, which most modern schedulers are designed with at the top of mind. All threads, aside from the one currently executing, are stuck waiting and are unable to progress at all until the current thread is finished. Moreover, when workloads are I/O-bound as opposed to CPU-bound (meaning that the thread’s execution time is constrained primarily by waiting for I/O devices like the disk or network links rather than the time it takes for the CPU to perform logic or arithmetic), threads tend to waste CPU cycles waiting without doing anything productive, holding up all the other threads as well.

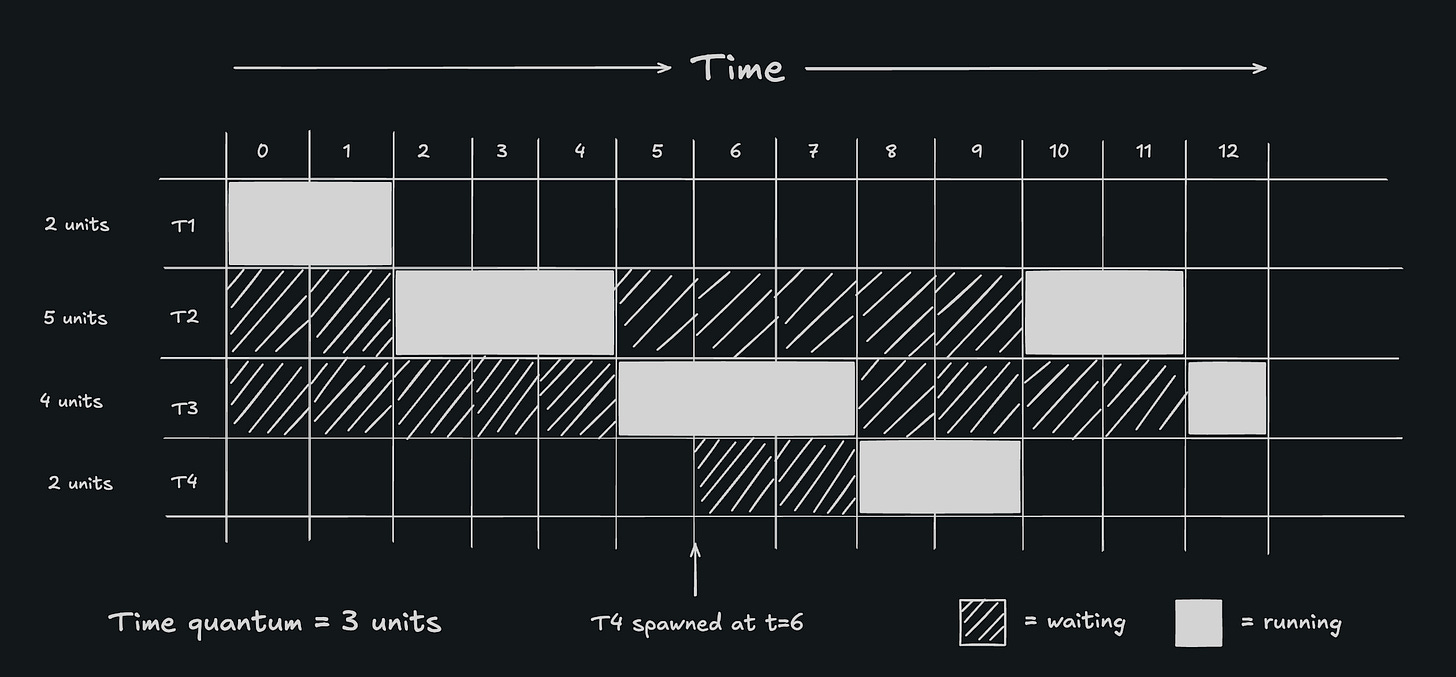

Round-robin is a different approach that attempts to maintain fairness and avoid wasting CPU cycles by interleaving the execution of threads. In essence, threads are placed in a queue, and each thread is given a predetermined number of CPU cycles to run (known as the time quantum) before being “paused” to allow the next thread in the queue to run. Threads return to the back of the queue only if they have not completed their task. This repeats for each thread in the queue. Note that round-robin isn’t the same as FIFO (first-in, first-out) semantics. If a new thread is introduced, it gets time to run first before older threads that have already (partially) executed. There are also more advanced approaches that allow each thread to have a different priority, and execution is given to the highest-priority thread currently available. The running thread can be interrupted if another thread with a higher priority becomes available.

With how fast modern CPUs have become, the rapid interleaving of multiple threads effectively allows for multitasking.

Example of round-robin scheduling

The scheduler, however, isn’t responsible for physically stopping and resuming different threads and processes. The scheduler’s only responsibility is deciding what gets to run at any given moment in time. Another component of the OS, known as the dispatcher, handles the changes in state that threads undergo as they are scheduled in and out of execution. The example above shows how threads change between a "running” and a “waiting” state. Implicitly in the diagram above, there is another “terminated” state that a thread reaches once its execution is complete, as is the case with T1 at t=2 or T3 at t=13, for example. What isn’t shown above but is still noteworthy is the idea of a “blocked” state, which is where a thread is unable to continue its execution due to something external that is preventing it from moving forward. One common example of a case where a thread gets blocked is when it has to wait for an I/O response (e.g., data from a database or across the network). Since the thread has to wait for something external, it’s usually more efficient to allocate CPU cycles to another thread in the meantime, which modern schedulers are designed with in mind. Another situation where a thread can get blocked is when it has to synchronize with other threads, often done to mitigate some of the issues that arise with concurrency, which we’ll explore in another article.

pre-emption, interrupts, and context-switching

When one thread has completed its turn, it has to “pause” for the next thread in the queue to execute. This “pausing” is more formally known as pre-emption. Pre-emption involves two parts: an interrupt and a context switch. The interrupt is a signal from the operating system to the currently executing thread, indicating that it must stop what it’s doing. When a thread has used its time quantum or when it triggers an I/O operation, an interrupt pauses it. Since this is a privileged operation, the OS has to enter kernel space and make a system call to invoke an interrupt, which is why interrupts tend to increase latency.

When a thread is interrupted, it must be able to resume later and pick up where it left off. Thus, upon receiving an interrupt, the executing thread’s context, including its register values (e.g., stack pointer, program counter, etc.) are saved in memory to allow the next thread to take over. This is known as a context switch. When the first thread is ready to resume again, the dispatcher reloads that thread’s register values previously saved in memory so that the thread can continue where it left off.

process and thread control blocks

One more important detail to note regarding threads and scheduling is that the scheduler uses special data structures to help manage the scheduling and preemption of processes and threads. These structures are known as process control blocks (PCBs) and thread control blocks (TCBs), respectively. A PCB/TCB stores relevant data for a particular active process/thread, including identifier data, state, and control data. While the exact kinds of data stored by these structures vary across systems, PCBs and TCBs typically consist of data such as a process/thread ID, the ID of the parent process, register contents, and scheduling state (e.g., “ready”, “blocked”, etc.), to name a few.

threading overhead

Multithreading is often associated with a performance increase as a result of dealing with multiple things at once. Sometimes this turns out to be the case, but threads don’t come for free. In practice, adding more threads to a concurrent program can plateau in performance and can eventually degrade program performance altogether. For one, spawning a thread requires a stack space to be allocated for it, which could occupy somewhere in the range of a few megabytes in size. Even just a thousand threads can occupy several gigabytes of memory. The acts of spawning and destroying threads each invoke a system call, requiring the OS to enter kernel mode, which incurs additional latency.

Context-switching is where the bulk of multithreading performance overhead stems from. When there are more threads than there are cores on the system, the scheduler has to switch context more often. Since the scheduler optimizes for fairness, each thread then only receives a small share of the CPU (i.e., CPU contention). Naturally, the share of CPU that each thread receives decreases as thread counts scale.

Schedulers don’t only decide what thread gets to run at any given moment, but they also decide where a scheduled thread gets to run. This is because schedulers are not only optimized for fairness, but also for maximal resource utilization. If the CPU contains multiple cores, as most modern processors do, it’s wasteful to have threads only run on one of them while leaving the other cores idle. Thus, multiple threads, even those within the same process, can run on different cores. As a result, context-switching can occur between threads of the same process or between those of different processes. Context-switching within the same process is typically cheaper than context-switching between processes, since threads share some of the same resources, such as heap memory and page tables. Since each process has its own virtual address space (see note below), process-level switching causes the given CPU core to flush (clear) its TLB (translation lookaside buffer) either completely or partially, depending on the system. When address translations are absent from the TLB, the CPU has to traverse the page tables instead to obtain memory address translations, which is more costly. Context-switching within the same process, however, is less costly because threads in the same process share the same virtual address space, hence why no TLB flush is required here.

Note: The TLB is a cache contained in the CPU’s MMU (Memory Management Unit), which is a piece of hardware responsible for translating virtual memory addresses into physical addresses using the process’s page tables. Since traversing page tables can be time-consuming, the TLB stores recent translations between virtual and physical memory addresses for faster access.

The nature of CPU caches plays a critical role in context-switching performance overhead. CPUs contain caches (L1, L2, and L3) that store recently accessed data so they can be accessed again more quickly compared to accessing from memory. The concept of cache locality refers to the idea that recently accessed memory is likely to be accessed again in the near future, which is why CPUs are designed to evict data from their caches that haven’t been used recently to make room for more recent data. This design is meant to reduce memory accesses for faster performance.

Context-switching prevents threads from leveraging cache locality, and the extent to which it hinders it depends on how data is being accessed. Context-switching between processes has a substantial performance impact, since each process has its own address space (and thus its own data that is inaccessible to other processes), causing the threads from the newly scheduled process to evict existing cache values and replace them with data from the new process. When the old process is rescheduled, all of its previously cached data is gone, forcing it to read from memory, which is slower. Eventually, the cache can fill back up with that process’s data again, but by then, the scheduler may have already decided to pre-empt that process, thus repeating the cycle of cache evictions. This ends up slowing down all threads running on the system. Context-switching between threads in the same process typically does not obstruct cache locality to the same degree, since threads in the same process often operate on shared data. Thus, when one thread reads from or writes to a global/static variable, that data stays warm in cache, allowing the newly scheduled thread (within the same process) to access that data faster when it receives its turn to be scheduled. Since each thread has its own stack, more stack-allocated variables on those threads correlate to worse cache locality and slower performance.

It should be clear now why threads are heavyweight. Switching between threads is inefficient due to their memory overhead, and the OS slows down if there are too many of them. Context switching, particularly between threads from different processes, prevents CPUs from capitalizing on cache locality as they were designed to. The result is wasted resources, reduced throughput, and increased latency.

making threads scale

thread pools

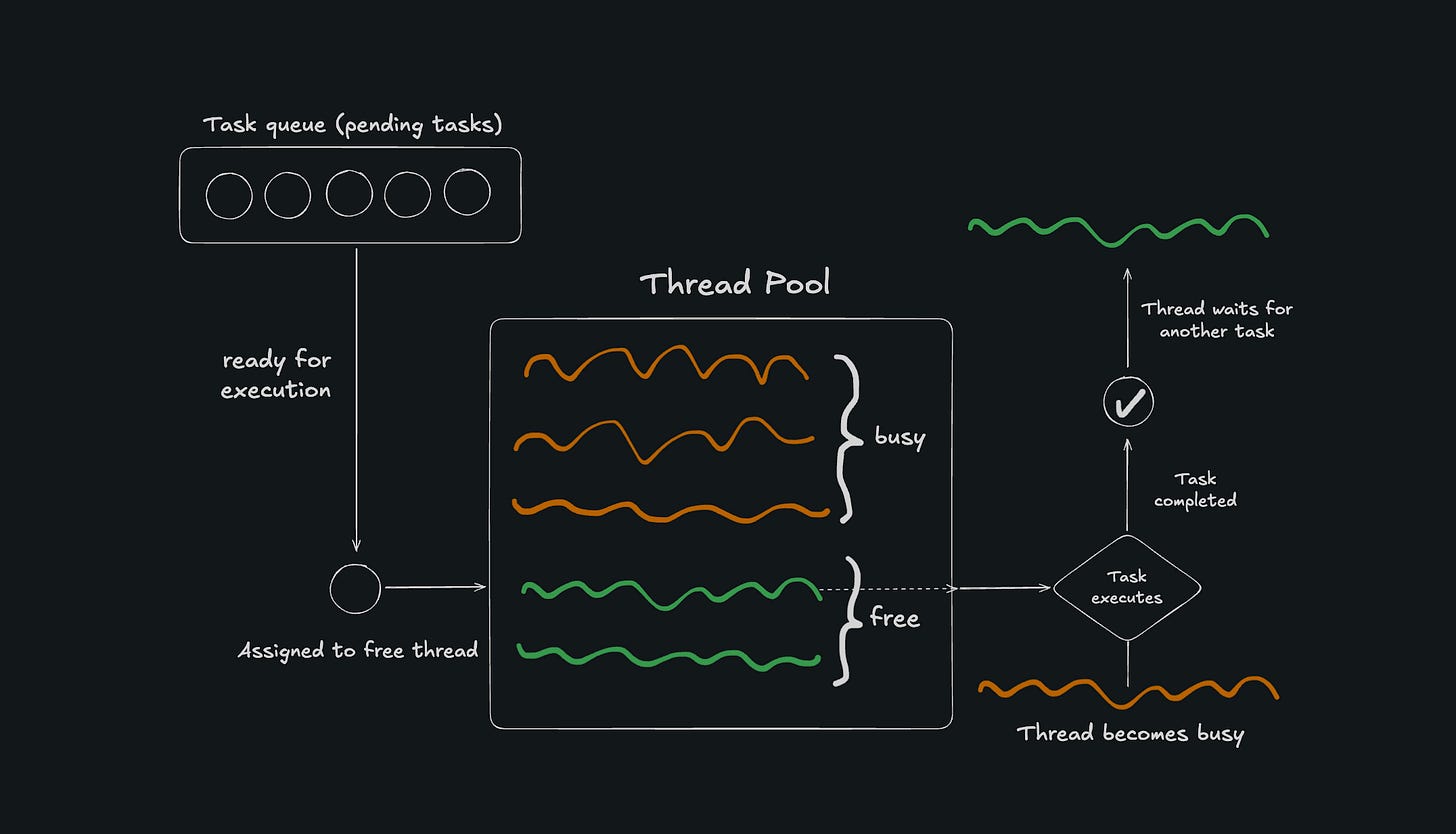

Scaling concurrent workloads becomes challenging since simply spawning more threads eventually becomes infeasible. Short-lived threads, when approaching the thousands, begin to incur meaningful performance degradation. To reduce the latency incurred by repeatedly spawning and destroying threads, it helps to reuse threads after they’re finished being used, to avoid the extra system calls and stack allocations. This is the essence of thread pools, which is a design pattern that pre-initializes several threads that functions can use for their execution before returning them to the pool to be reused later by another function. Thread pools typically maintain a FIFO (first-in, first-out) queue for tasks that need to be executed. The threads in the pool run in a continuous loop, remaining idle as they watch the task queue, pull tasks as they become available, and execute those tasks before they return to being idle. Throughout a given task’s execution, no other task can use that thread. Once the running task is complete, the thread is freed up so it can be used by another task.

Reusing threads prevents additional system calls and stack allocations, and by reducing thread counts, reduces CPU contention and context-switching. Thus, thread pools typically allow for more efficient thread scaling.

Some thread pool implementations contain a fixed number of threads, while others can grow and shrink the thread count as needed. The ThreadPoolTaskExecutor class in Java, for instance, allows a corePoolSize (the default number of threads), and a maxPoolSize (the maximum number of threads the pool can accommodate) to be specified. The thread pool spawns or destroys threads based on the workload, staying within these two bounds. The Spring Boot framework, a popular web framework for Java, uses a ThreadPoolTaskExecutor to load-balance incoming concurrent HTTP requests onto multiple threads while retaining strong performance.

thread affinity

As mentioned above, the scheduler may choose to run a thread on any CPU core to ensure maximal resource utilization. This results in worse cache locality and slower data access. To mitigate this problem, programmers can use a technique known as thread affinity (also called “CPU pinning”). Thread affinity ensures that the threads of a given process are run on the same core or the same set of cores. This is meant to prevent the scheduler from bouncing threads between cores with different caches, and in theory helps to reduce cache misses.

This example shows how to pin a thread to a particular CPU core on a Linux system in C++, taken from C++ High Performance by Viktor Sehr and Bjorn Andrist. Note that implementing thread affinity is OS-specific, and thus must be rewritten for other OSes:

#include <pthreads> // Non-portable header

auto set_affinity(const std::thread& t, int cpu) {

cpu_set_t cpuset;

CPU_ZERO(&cpuset);

CPU_SET(cpu, &cpuset);

pthread_t native_thread = t.native_handle();

pthread_set_affinity(native_thread, sizeof(cpu_set_t), &cpuset);

} (multicore) parallelism

Concurrency is about handling multiple things at once, which is done by a rapid interleaving of threads via the scheduler. When multiple cores are present, threads can run on separate cores. Given that each core provides the resources necessary for doing work (e.g. registers, ALUs, etc.), threads running on different cores can run at the same time. In other words, they are said to run in parallel. Parallelism, then, is a special type of concurrency in which multiple things are being done simultaneously and allows for an even greater (theoretical) performance gain. Once again, the distinction between concurrency and parallelism is between program structure and execution. Implementing concurrency boils down to reasoning about a different way of structuring your program, whereas parallelism is more tied to the way the program is running. If multiple cores are available, the scheduler will attempt to take advantage of them and run threads on multiple cores, but aside from thread affinity, we as programmers usually can’t dictate how and where the scheduler schedules threads. Parallelism can be implemented, however, by spawning multiple processes at once, as seen with the multiprocessing module in Python.

models of concurrency

Threading is only one of multiple possible approaches for implementing concurrency. Languages like C, C++, and Java gravitate toward this model quite heavily, whereas concurrency in other languages may look different. In fact, Python, for example, includes a Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) that effectively prevents multithreading entirely.

As developers, threads provide a relatively simple way to reason about dealing with multiple things at the same time. As mentioned above, multithreading is not a panacea. Scaling threads comes with more memory overhead, CPU contention, system call latency, rapid context-switching, and poor cache utilization. Given what we know about threads, one may ask whether there are different methods of achieving concurrency that can overcome these limitations. In the remainder of this Discourse, we’ll examine what these models of concurrency look like, along with some challenges that can damage the performance or correctness of concurrent programs.